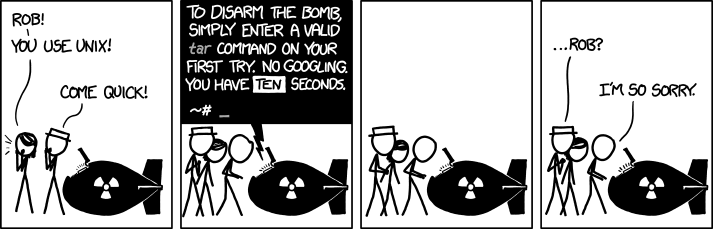

Do You Speak Tar?

For a lot of people, the GNU tar command’s options seem obscure and hard to

use. The most common ones exist only in a short form and always appear grouped

in the same order and often without a leading hyphen, e.g. tar xzvf

archive.tgz and not tar -v -z -x -f archive.tgz. Additionally, tar doesn’t

work without any “option”.

These options, or rather these commands, can be seen as a (small) language that

you can learn to speak, write or read. Each command has its own

meaning that sometimes depend on which other commands are used with it.

The Grammar

tar’s sentences start with a verb. There’s no subject, because you’re giving

an order to tar. This verb is followed by zero or more modifiers that give

more context to the action. The last part is the object(s) on which the action

is made. Spaces are not needed between tar’s words because they all consist

of one letter.

Actions

The two most common actions are “create” (c) and “extract”

(x). The first one is used to create an archive from some files; and the

second is used to extract that archive in order to get back those files.

All tar implementations support one more action: “list” (t) to

list an archive’s content without extracting it. Some implementations support

two variants of “create” that are “append” (r) and “update”

(u). The former appends files to an existing archive; the latter updates

files in the archive for which there exist a more recent version.

Unfortunately we now know all tar actions but can’t do much without knowing

how to apply them to an object. Let’s dive into objects and we’ll see the

modifiers later.

Objects

tar has a very limited set of objects: archives. Each tar command operates

on one archive, that is given by f (for “file”) followed by its path.

Files added or extracted from archives are simply given as extra arguments to these commands without needing any special word.

We’re now ready to write our first meaningful sentences.

“Hey tar, please create an archive file foo.tar with file1

and file2” is written as tar cf foo.tar file1 file2.

“Extract archive file foo.tar” is written as tar xf foo.tar.

“List archive file foo.tar” is written as tar tf foo.tar. You get

the idea.

Note that actions like “extract” or “list” accept additional

arguments for the file patterns you want to extract/list. Say you have a big

archive from which you only want to extract one important.txt file. Just give

this information to tar and it’ll kindly extract it for you:

tar xf big-archive.tar important.txt

You might wonder what is this “file” word for if we always need it.

Well, we can remove it. But if we do so, our tar command doesn’t have any

object left, so it’ll look at something else: STDIN or STDOUT.

Actions that read archives operate on STDIN if you don’t give them a

file object:

cat big-archive.tar | tar x important.txt

You can also be explicit by giving - to f:

cat big-archive.tar | tar xf - important.txt

The “create” action will output the archive on STDOUT if you don’t

give it a name (or use f -). You still need to give it the name of the files

to put in that archive:

tar c file1 file2 > archive.tar

# Same, but more explicit

tar cf - file1 file2 > archive.tar

Note that you can’t extract an archive to STDOUT without a modifier.

tar operates on files, not on data streams. By default it doesn’t compress

its content so creating a tar archive for one file doesn’t make much

sense.

Now that we know how to write basic sentences, let’s add some modifiers to them.

Modifiers

In my experience the most used modifiers are v and z. The first one is the

“verbose” flag and makes tar more chatty. When creating or

extracting an archive it’ll print each file’s name as it’s (un)archiving

it. When listing an archive it’ll print more info about each file.

Compare both outputs below:

$ tar tf archive.tar

file1

file2

$ tar tvf archive.tar

-rw-r--r-- 0 baptiste wheel 31425 18 sep 14:51 file1

-rw-r--r-- 0 baptiste wheel 18410 18 sep 14:51 file2

The v modifier can be combined with any other one mentioned below.

z will tell tar to use Gzip to (de)compress the archive. Nowadays

tar-ing with no compression is rarely used, and Gzip is ubiquitous. Just add

z to your modifiers and tar will create compressed archive and

extract them. The convention is to use .tar.gz or .tgz for such

archives:

tar czf archive.tar.gz file1 file2

# Later…

tar xzf archive.tar.gz

Other common modifiers include j that works exactly like z but (de)compress

using Bzip2 instead of Gzip. Such archives usually end with .tar.bz2 or

.tbz2. It’s not named b or B because those were already taken when

this modifier was introduced.

Similarly to j one can use its capital friend, J. This one compresses using

xz instead of the last Gzip or Bzip2. These archives use the extensions

.tar.xz or .txz.

Note you can also (de)compress archives by yourself if you don’t remember these modifiers:

tar cf myarchive.tar file1 file2

gzip myarchive.tar

# Later…

gunzip myarchive.tar

tar xf myarchive.tar

There is a dozen of other modifiers you can find in the manpage, but let’s

mention two more: O and k. You may remember from the first section that I

wrote you can’t extract an archive to STDOUT without a modifier. Well,

that modifier is called O:

tar xOf myarchive.tar

Using O when extracting will print the content of the archive on

STDOUT. This is the same output as you would get by calling cat on all the

files in it.

The last modifier I wanted to mention is k, which tells tar not to override

existing files when extracting an archive. That is, if you already have

a file called important.txt in your directory and you un-tar an archive

using the k modifier, you can be sure it won’t override your existing

important.txt file.

I hope this post helped you have a better understanding of tar commands, and

how they’re not that complicated. I put a few (valid) commands below, just so

you can see if you understand what’s they’re doing:

tar xf foo.tar

tar cvzf bar.tar a b c

tar tvf foo.tar important.txt

tar cz file1 file2 > somefile

tar xzOf somefile

tar cJf hey.txz you andyou

tar xkjvf onemore.tbz2